[ad_1]

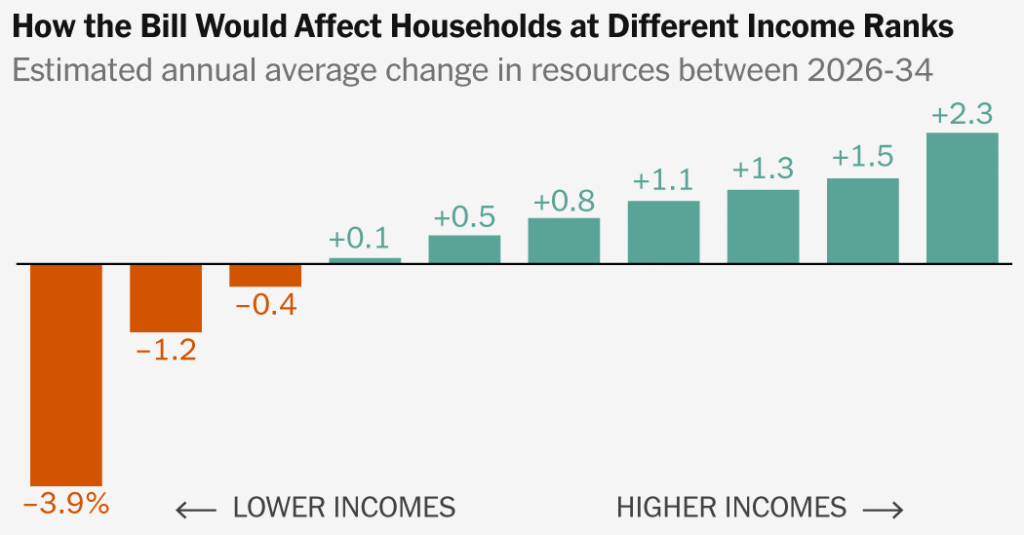

The Republican megabill now before the Senate cuts taxes for high earners and reduces benefits for the poor. If it’s enacted, that combination would make it more regressive than any major tax or entitlement law in decades.

How the Bill Would Affect Households at Different Income Ranks

Estimated annual average change in resources between 2026-34

The bill as passed by the House in May would raise after-tax incomes for the highest-earning 10 percent of American households on average by 2.3 percent a year over the next decade, while lowering incomes for the poorest tenth by 3.9 percent, according to new estimates by the Congressional Budget Office.

The shape of that distribution is rare: Tax cut packages have seldom left the poor significantly worse off. And bills that cut the safety net usually haven’t also included benefits for the rich. By inverting those precedents, congressional Republicans have created a bill unlike anything Washington has produced since deficit fears began to loom large in the 1990s.

“I’ve never seen anything that simultaneously really goes after poor people and then really helps rich people,” said Chuck Marr, the vice president for federal tax policy at the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

To the extent that some prior bills have also been regressive, they still haven’t looked quite like this.

Comparing Major Tax and Entitlement Bills

The G.O.P. plan is among the bills projected to benefit the highest-income group while hurting the lowest.

|

2025 |

Current G.O.P. bill |

Lose |

Gain |

|

2017 |

Obamacare repeal* |

Lose |

Gain |

|

1997 |

Tax and budget acts |

Unclear |

Gain |

|

1996 |

Welfare act |

Lose |

No change |

|

2022 |

Inflation Reduction Act |

Gain |

Lose |

|

2021 |

Build Back Better* |

Gain |

Lose |

|

2010 |

Affordable Care Act |

Gain |

Lose |

|

1993 |

Clinton budget act |

Gain |

Lose |

|

1990 |

H.W. Bush tax act |

Gain |

Lose |

|

2017 |

First Trump tax cuts |

Gain |

Gain most |

|

2013 |

Obama tax cuts |

Gain |

Gain most |

|

2001/03 |

W. Bush tax cuts |

Gain |

Gain most |

The calculations the C.B.O. published are what’s known as a distributional analysis. This type of study estimates how legislation will affect people across the income distribution, taking into account the taxes they pay and the government benefits they receive. Lawmakers often think about legislation in terms of its overall effects: Does it raise or lower the deficit? Does it grow or stifle the economy? But this kind of analysis helps illustrate who benefits and who is hurt by a bill.

“Ultimately, people care about who are the winners and who are the losers,” said Alan Auerbach, a professor of economics and law at the University of California, Berkeley, who has studied fiscal policy for decades.

Stephen Miran, chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, dismissed the C.B.O.’s analysis as missing who those winners are in the bigger picture.

“The best way to help workers across the income distribution, including all the folks in the bottom, is to create an environment in which firms want to hire them,” he said, pointing to rising wages and low unemployment after the passage of the major tax cut package during the first Trump administration. He disputed that low-wage workers would now be hurt in this bill by changes to Medicaid and food assistance.

To put the current bill in context, we have assembled similar analyses of major tax and social welfare bills from the last four decades.

The analyses below aren’t all exactly the same. Most were originally published around the time each bill was debated in Congress. They were produced by a few different analysts, because no one group has routinely published distributional tables. They don’t always cover every provision in every bill, which means some charts may be missing a few relevant effects. They evaluated slightly different time windows after enactment. In cases where we lacked complete data, we have not shown a complete chart, but instead characterized a bill’s effects on the highest- and lowest-income households.

Compared with other legislation, this bill is notable because it’s so regressive — while neither reducing the deficit nor supercharging growth, according to analysts across the political spectrum.

“This bill definitely compromises too much on growth, and it doesn’t make smart use of tax cuts either,” said Erica York, vice president for federal tax policy at the Tax Foundation, a research group that generally favors lower taxes. “If you look at the revenue cost, it’s really large. If you look at the economic impact, it’s not that meaningful.”

Regressive bills

Since 1990, there have been a couple of other major bills that leave the poor worse off, but they differ from the current proposal in key ways.

The current bill cuts health care spending, food assistance and other programs that benefit the poor, in addition to extending tax cuts for individuals that passed in 2017. Those 2017 tax changes, on average, benefited all income groups, but were skewed toward higher earners. New tax policies in the current bill would shift those benefits up the income scale even more. And some new tax provisions that would help lower-income households — like no tax on tips and no tax on overtime — would expire after a few years, while many benefits for high earners would be made lasting.

“That makes this specific episode kind of exceptional,” said Owen Zidar, a Princeton economist. “We just don’t usually have big tax cuts running in different directions from the bottom than at the top.”

Mr. Zidar noted that one tax provision that mostly benefits the rich — an expansion of the tax deduction for certain types of business income — is estimated to cost about as much as the bill’s major reductions in Medicaid spending would save.

Republicans’ attempted repeal of Obamacare (2017, not enacted)

Bottom earners would lose; top earners would gain